HPV DNA or HPV E6/E7 mRNA assays?

Currently, more than 200 commercial test meth- ods are available for the detection of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) in cervical swab samples. These tests largely differ in the test principle, the detection of HPV DNA or RNA, as well as the targeted viral genome region.1 While some test methods are limited to the detection of the so- called high-risk (hr) HPV types, which are classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as carcinogenic to humans, there are also several test methods that additionally identify the two HPV types 16 and 18, as well as aggregate of other high- risk types, since the former two types have the highest risk potential for cervical cancer. In addition, there are numerous tests that are based on various methodologies and that allow more extended genotyping. Only one commercially available test allows detection of viral activity by targeting transcripts of the oncogenes E6 and E7 from all high-risk types: APTIMA HPV (Hologic, Bedford, MA, USA).

When comparing HPV DNA- and RNA-based detection methods, it is important to consider that the detection limit from which a test indicates a positive result, as defined by the manufacturer, is not primarily determined by the analytical sensitivity of the respective test. Rather, the detection limit should be determined in clinical trials in which an optimal ratio of clinical sensitivity to clinical specificity determines the cut-off, i.e. the threshold for a positive test result. Thus, all test methods that aim at maximum sensitivity are not suitable for use in early detection cervical cancer screening programs, because they would detect a large number of “latent infections”, which are not clinically significant and would lead to unnecessary follow-up investigations for the women, individual uncertainty and unnecessary costs for health care systems.

To avoid the requirement for each new HPV test to prove its performance in large clinical trials, an international expert group established guidelines for new HPV testing methods used for cervical cancer screening.2These guidelines consider the HC2 (Digene Hybrid Capture 2 High-Risk HPV DNA Test (Qiagen)) or GP5+/6+ PCR as standard comparator tests. These two tests have demonstrated superior protection against future CIN3+ and cancer when used in primary screen- ing than good-quality cytology.3,4

The guidelines call for a non-inferior clinical sensitivity and clinical specificity, accepting the bench marks 0.9 for relative sensitivity and 0.98, for relative specificity compared to the HC2 test or GP5+/6+ EIAPCR. Furthermore, comparative studies should be performed using cervical specimens from a representative routine screening population of women who are at least 30 years old. In addition, the study cohort should contain at least 60 cases of precancerous lesions (Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia Grade 2, CIN2+) as well as a minimum of 800 smears of females with no severe lesions (≤CIN1). Moreover, the new test method is expected to achieve a high intra- and inter-laboratory reproducibility of at least 87%. The evaluation of a novel test after performing these studies should be car- ried out with a “non-inferiority” test.2 Although these guidelines are undoubtedly helpful, they might no longer be sufficient to justify the use of an HPV test procedure in the cervical cancer screen- ing programs coming ahead. New HPV tests introduced in screening will need to be monitored carefully to verify longitudinal performance in mass screening conditions and replaced or adjusted when required. Finally, novel test methodologies require acceptance by competent regulatory bodies involving experts and stakeholders, and be economically affordable.

In the United States, most of these criteria are specifically examined by the FDA during their approval process. In Europe, no comparable authorization procedure exists. However, validation protocols such as VALGENT5 or Meijer2 are widely accepted. The Directive 98/79/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 October 1998 on in-vitro diagnostic medical devices (CE marking) only requires proof of conformity of new methods for the detection of HPV, which is not comparable to the certification process of the FDA. However, even FDA-approved HPV tests do not necessarily meet all the requirements for application in cervical cancer screening programs as demonstrated by a study comparing an FDA approved DNA-test (Cervista, Hologic) that showed twice as high HPV positivity rate in cytologically normal women compared to HC2. By increasing the cut-off, this lack of clinical specificity could be remedied without loss of sensitivity.6,7 However, in the US this change would require a new approval by the FDA.

Logically, perhaps a test that detects the activity of the viral oncogenes by detecting viral mRNA should be more specific than tests merely detect- ing HPV DNA, which might be present in the form of viral particles even outside of cells and therefore does not necessarily indicate disease or even HPV infection. In fact, published studies show a sensitivity of the RNA-based test comparable to the HC2 (ratio of 0.98 (CI 0.95–1.01), together with a significantly increased specificity (ratio 1.04 (CI 1.02–1.07) of the RNA test.5 This increased specificity will result in a considerable reduction (23%) of follow-up investigations due to a positive test result and therefore decrease costs for follow-up.8

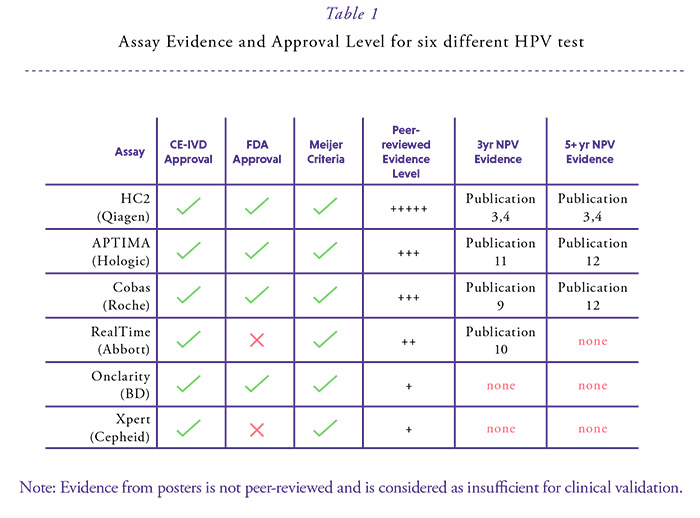

Many countries have or are about to introduce HPV-based cervical cancer screening. For three DNA tests based on the detection of the whole genome or the genomic region coding for the main capsid protein and the RNA test for group detection of the E6/E7 mRNA of the high-risk HPV types, data from prospective studies have become available over at least three years suggesting comparable safety to the standard comparator test over this interval (Table 1).9-11 All of these tests also allow the possibility to simultaneously or subsequently detect HPV16/18. This provides a possibility to triage the primary result to evaluate the individual risk for CIN2+ in HPV-positive women.

All commercially available HPV test methods in Europe must be CE-marked. However, the CE mark does not represent a certification for a test to be used in cervical cancer screening programs. For the large majority of available HPV tests, even no published data exist. The criteria required by Meijer et al.2 concern only HPV DNA assays which are today met for only a few ones5 (this issue page 6) of which four have received FDA approval for the US market. However, FDA approval is not relevant in Europe and even this approval does not guarantee the suitability for mass screening. Therefore, HPV tests used in primary screening in Europe should be reclassified to meet the requirements of Class C high-risk IVDs in accordance with the requirements of the International Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF,http:// www.imdrf.org/).

In summary numerous studies from different populations (screening, referral) consistently demonstrated a similar cross-sectional sensitivity paired with higher clinical specificity when APTIMA was compared to other FDA approved HPV DNA tests, which reduces the burden of follow-up. Since APTIMA is not a DNA test, longitudinal performance over a 5-year period is still required; which may be available in the near future. Once this level of evidence is reflected in the peer-reviewed literature, APTIMA might become a preferred assay for cervical cancer screening. Just at the moment of publication of this HPV World paper non-inferior longitudinal (over 5-7 years) sensitivity of APTIMA compared to the FDA approved cobas 4800 was demonstrated in a Swedish biobank linkage study.12

References

1. Poljak M, Cuzick J, Kocjan BJ, et al. Nucleic acid tests for the detection of human papillomaviruses. Vaccine 2012;30 (Suppl 5): F100-F106.

2. Meijer CJLM, Castle PE, Hesselink AT, et al. Guidelines for human papillomavirus DNA test requirements for primary cervical cancer screening in women 30 years and older. Int J Cancer 2009;124: 516-20.

3. Arbyn M, Ronco G, Anttila A, et al. Evidence regarding HPV testing in secondary prevention of cervical cancer. Vaccine 2012;30 Suppl 5: F88-F99.

4. Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfstrom KM, et al. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2014;383: 524-32.

5. Arbyn M, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJLM, et al. Which high-risk HPV assays fulfil criteria for use in primary cervical cancer screening? Clin Microbiol Infect 2015;21: 817-26.

6. Boehmer G, Wang L, Iftner A, et al. A population-based observational study comparing Cervista and Hybrid Capture 2 methods: improved relative specificity of the Cervista assay by increasing its cut-off. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14: 674.

7. Boers A, Slagter-Menkema L, van Hemel BM, et al. Comparing the Cervista HPV HR Test and Hybrid Capture 2 Assay in a Dutch Screening Population: Improved Specificity of the Cervista HPV HR Test by Changing the Cut-Off. PLoS ONE 2014;9: e101930.

8. Haedicke J, Iftner T. A review of the clinical performance of the Aptima HPV assay. J Clin Virol 2016;76 Suppl 1: S40-S48.

9. Wright TC, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, et al. Primary cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus: End of study results from the ATHENA study using HPV as the first-line screening test. Gynecol Oncol 2015;136: 189-97.

10. Poljak M, Ostrbenk A, Seme K, et al. Three-year longitudinal data on the clinical performance of the Abbott RealTime High Risk HPV test in a cervical cancer screening setting. J Clin Virol 2016;76 Suppl 1: S29-S39.

11. Reid JL, Wright TC, Jr., Stoler MH, et al. Human papillomavirus oncogenic mRNA testing for cervical cancer screening: baseline and longitudinal results from the CLEAR study. Am J Clin Pathol 2015;144: 473-83.

12. Forslund O, Miriam EK, Lamin H, et al. HPV-mRNA and HPV-DNA detection in samples taken up to seven years before severe dysplasia of cervix uteri. Int J Cancer 2018.