The Pap Test Beyond Cervical Cancer Screening

Cervico-vaginal cytology (ie, Pap test) is a well-established cervical cancer screening method. Large reductions in cervical cancer burden have been achieved in developed countries through organized public health programs that offer the Pap test several times over the course of a woman’s life to increase its moderate sensitivity.

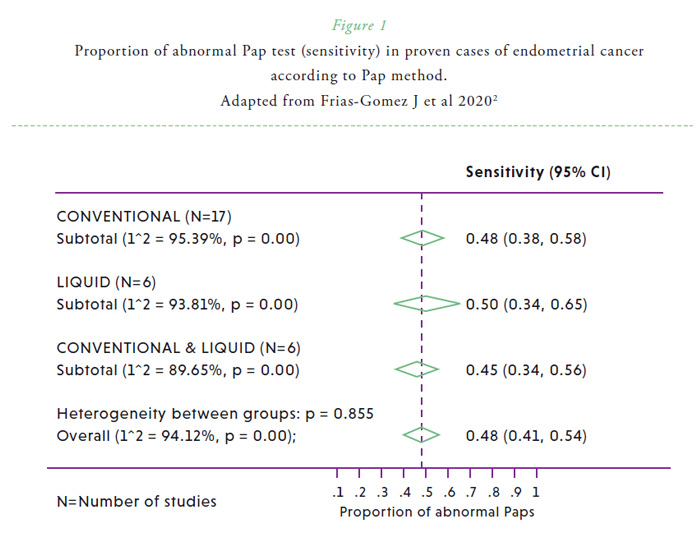

The anatomical continuity of the uterine cavity with the cervix and the vagina makes it accessible to evaluate signs of disease shed from the upper genital tract. At the end of his career, George Papanicolaou, the inventor of the Pap test, became interested in the diagnostic value of cervico-vaginal smears in the detection of endometrial cancer.1 However, he acknowledged that cytology was not equally satisfactory in the detection of endometrial cancer compared with cervical malignancies. While cytological epithelial abnormalities are commonly observed in cervical cancer and its precursors, glandular abnormalities (such as endometrial adenocarcinoma cells, atypical glandular cells, or endometrial cells in women 40 years of age or over) are seldom observed in cervical cytologies in women with endometrial cancer. A recent systematic review, which evaluated 6599 women with endometrial cancer from 45 studies, revealed that 45% (95% CI, 40%-50%) of study participants had abnormal Pap test results prior to diagnosis of or surgery for endometrial carcinoma.2 This percentage was significantly higher among those of advanced cancers and less favorable histologies, and there were not statistically significant differences between conventional and liquid-based methods (Figure 1).2

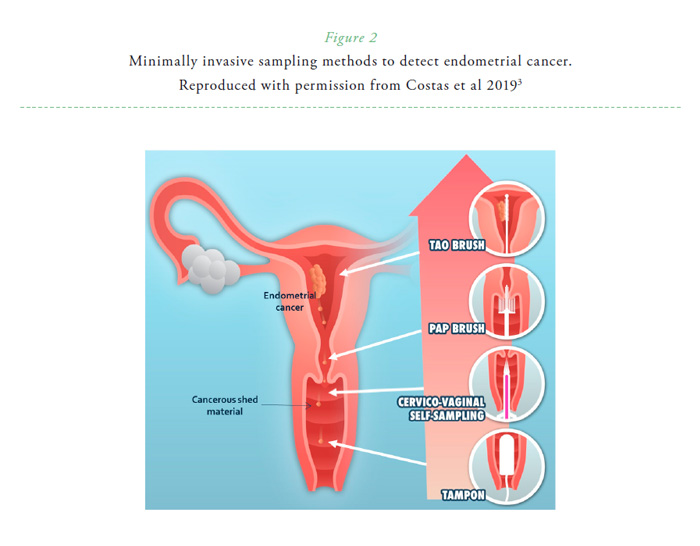

The introduction of liquid-based technologies in the past years has allowed the possibility of molecular testing in the same specimen. This includes HPV testing, but also the evaluation of genomic biomarkers characteristic of other gynecological cancers. Thus, different studies have addressed its potential detecting other diseases than cervical cancer and precursors.3 Molecular testing allows evaluating early signs of disease with a greater sensitivity than the morphologic evaluation of the material, and therefore, using the Pap test as a minimally invasive sampling method to detect distant gynecologic cancers, such as endometrial and ovarian cancers (Figure 2). Few proof-of-concepts in reduced sample sizes have shown feasibility to discriminate between endometrial cancer and benign conditions in Pap brush samples using genomics, proteomics or epigenomics with high sensitivity (Table 1).3 In a large sample size (382 cancer cases and 714 controls), Wang et al. used a sensitive targeted sequencing technology, which covers 9392 distinct nucleotide positions within 139 regions of 18 genes of interest. Using Pap brush samples, 81% (95% CI, 77%-85%) of endometrial cancer cases were identified using this test4. In this same study, sensitivity to detect ovarian cancer using Pap brush samples was 33% (95% CI, 27%-39%).4

Cervico-vaginal self-sampling is being implemented in many settings to increase cervical cancer screening coverage and is being offered as an alternative screening approach in some regions. A relevant research question is therefore to evaluate if signs of endometrial disease could also be detected in these cervico-vaginal self-sampled specimens. A recent study revealed that mutational analysis (evaluating regions from 8 characteristic genes) of Pap brush samples and self-samples obtained a sensitivity of 78% (95% CI, 64–88%) and 67% (95% CI, 53–79%) respectively, with a specificity of 97% (95% CI, 83–100%) for both type of samples.5

Several questions need to be addressed in order to accelerate the implementation of these novel technologies in a routine screening or clinical setting. These include the cost-effectiveness of related strategies, the potential detection of precursor lesions of these gynecological cancers, and the potential change on disease outcomes by the detection of early lesions, among others.3

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare nothing to disclose.

References

1. Papanicolaou GN, Maddi FV. Diagnostic value of cells of endometrial and ovarian origin in human tissue cultures. Acta Cytol 1961;5:1–16. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/13732618/

2. Frias-Gomez J, Benavente Y, Ponce J et al. Sensitivity of cervico-vaginal cytology in endometrial carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Cytopathol 2020. doi.org/10.1002/cncy.22266. Online ahead of print. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32202704/

3. Costas L, Frias-Gomez J, Guardiola M et al. New perspectives on screening and early detection of endometrial cancer. Int J Cancer 2019;145:3194–3206. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31199503/

4. Wang Y, Li L, Douville C et al . Evaluation of liquid from the Papanicolaou test and other liquid biopsies for the detection of endometrial and ovarian cancers. Sci Transl Med 2018;10:eaap8793. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29563323/

5. Reijnen C, van der Putten LJM, Bulten J et al. Mutational analysis of cervical cytology improves diagnosis of endometrial cancer: A prospective multicentre cohort study. Int J Cancer 2019;146(9):2628-2635. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31523803/