Natural history, from oral HPV infection to HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer

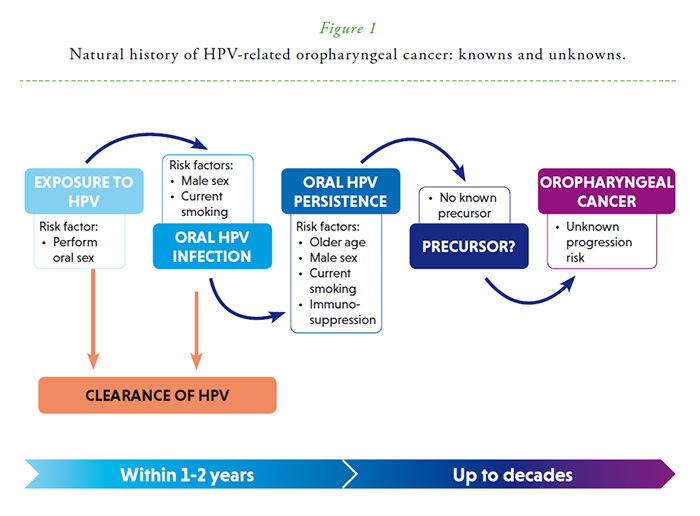

Oral HPV infection is the obligate cause of HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer (HPV-OPC), whose incidence is increasing in several countries. HPV16 causes over 85-90% of HPV-OPC. Markers of HPV16 exposure, such as prevalent oral infection and HVP16 L1 or E6 seropositivity, are associated with a 50-150-fold odds/risk of HPV-OPC. However, the natural history of oral HPV infection, spanning the initial establishment of infection and the later development of cancer (Figure 1), remains poorly characterized, because few natural history studies have been conducted to date. Nonetheless, initial longitudinal studies evaluating HPV DNA in oral rinse samples show key similarities, as well as some differences, in the epidemiology of oral HPV infections compared to cervical/anogenital HPV infection.

Oral HPV infection is primarily acquired through sexual activity (performance of oral sex). Oral HPV infection is rare in the absence of reported sexual behavior and prevalence/incidence increase substantially in individuals with high lifetime and recent oral sexual partners. Incidence rates for oral HPV infections in the literature range from 0.5-44 per 100 person-years1 (cumulative incidence 5/per 12 person-months).2 The per-partner incidence rate of oral HPV infection appears lower than anogenital HPV infection, which could explain lower prevalence of oral HPV16 when compared to cervical HPV16. Oral HPV incidence is approximately stable with age, and is higher in men, smokers, and immunosuppressed HIV-infected individuals. As with cervical/anogenital HPV infections, most oral HPV infections (~70-90%) clear within 1-2 years, although some infections persist for many years. Risk factors for oral HPV persistence include older age, male gender, current smoking, and HIV co-infection. Immunologic susceptibility potentially explains the lack of age-related decline in oral HPV incidence, increased persistence with older age, and the observed associations of oral HPV incidence and persistence with male gender, current smoking, and HIV infection.3

Importantly, in the oropharynx, there is no recognized HPV-induced precancer, analogous to CIN2/3 or AIN2/3. This lack of a pathologically-defined precancerous state may be related to the unique architecture of the tonsillar crypt epithelium—a non-differentiating reticulated epithelium with large pockets of exposed basal layer and discontinuous basement membrane. Due to the lack of large, long-term natural history studies and an HPV-induced intermediate disease state, screening for HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer is not feasible at this time. Likewise, estimates for many important questions remain unknown including time from acquisition of causal HPV infection to HPV-OPC, disease latency, and transition probabilities for progression from persistent infection to precancer and invasive cancer. Data from nested case-control studies of HPV16 L1/E6 antibodies suggest latency of 10+ years for progression to HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer.

Oropharyngeal cancer remains a relatively rare cancer (Figure 2), although the incidence is increasing in some countries. The proportion of OPC attributed to HPV is high in some countries, especially in settings with lower rates of tobacco and alcohol use (the other primary risk factors for oropharyngeal cancer), but low in other countries.4 There is a great need in the field for large natural history studies in diverse populations to characterize the steps from acquisition of oral HPV infection to progression to HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers. Such knowledge remains critical for both primary prevention through prophylactic HPV vaccination (i.e. determination of the appropriate upper age-limit for vaccination) as well as secondary prevention and early detection through screening.

DISCLOSUREThe authors declare nothing to disclose.

Reproduced with permission from the International Agency for Research on Cancer and the World Health Organization.

ARTICLES INCLUDED IN THE HPW SPECIAL ISSUE ON HPV IN OROPHARYNGEAL CANCER:

AR Kreimer, T Waterboer. Screening for HPV-driven oropharyngeal cancer

M Taberna, R Mesia, RL Ferris. Clinical management of HPV-related recurrent/metastatic (R/M) oropharyngeal cancer patients

MJ Windon, EM Rettig. Counseling patients with a diagnosis of human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal cancer

S Huang. Oropharyngeal carcinomas: the UICC/AJCC TNM staging system, 8th edition

AR Kreimer, A Chaturvedi. Will HPV vaccines reduce oropharyngeal cancer burden?

References

1. Taylor S, Bunge E, Bakker M et al. The incidence, clearance and persistence of non-cervical human papillomavirus infections: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis 2016;16:293. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27301867/

2. Wood ZC, Bain CJ, Smith DD et al. Oral human papillomavirus infection incidence and clearance: a systematic review of the literature. J Gen Virol 2017;98(4):519–526. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28150575/

3. Giuliano AR, Nyitray AG, Kreimer AR et al. EUROGIN 2014 roadmap: differences in human papillomavirus infection natural history, transmission and human papillomavirus-related cancer incidence by gender and anatomic site of infection. Int J Cancer 2015;136(12):2752–2760. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25043222/

4. Castellsagué X, Alemany L, Quer M et al. HPV Involvement in Head and Neck Cancers: Comprehensive Assessment of Biomarkers in 3680 Patients. J Natl Cancer Inst 2016;108(6):djv403. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26823521/